Gerlach, Burning Man, and Where It All Goes From Here

August 24, 2016

Making Sense of Fly Ranch — #2: Sound

November 14, 2017In this five-part blog series, Burning Man Project Land Fellow, Lisa Schile-Beers (a.k.a. Scirpus), will share the ecological survey work she is doing on Fly Ranch by using touch, taste, smell, sound and sight to frame her findings and guide you around the property. Burning Man’s Fellows program is an investment in people, leadership and innovation, and Lisa is the third Burning Man Fellow since 2015.

Over the past year, there has been much attention given to Burning Man’s acquisition of the Fly Ranch property and what will be done on the land.

Fly Ranch is located in the Hualapai Valley that’s just north-west of Black Rock City and borders the Hualapai’s own small playa, where the Burning Event occurred in 1997.

So, needless to say, this property has caught the attention of many over the years, yet much is unknown beyond the obvious sign of geothermal activity that everyone wants to take a selfie with.

One of the largest unknowns lies within the ecology of the property. What plants, birds, animals, fish, reptiles, invertebrates and heat-loving bacteria are here? How long do they stay? How much of the property really is a wetland and does a Swamp Thing live here too?

Tasks and Translation

For six months in 2017, I’m tasked with exploring these five square miles and documenting the flora, fauna, water, climate and the land in general. This has been no small feat considering the amazing diversity of the property.

I’ve studied plant ecology and carbon dynamics of wetlands from Alaska to Panama to the United Arab Emirates over the past 20 years, and I’m amazed by the surprising similarities and striking differences of wetlands in the Great Basin sagebrush steppe.

During the first month of my fellowship, a constant question kept popping up: how do I relay the data I’m collecting in a tangible and digestible way to the Burner community? And it occurred to me that the best way to do it was through how I experience it — the five senses.

During the first month of my fellowship, a constant question kept popping up: how do I relay the data I’m collecting in a tangible and digestible way to the Burner community? And it occurred to me that the best way to do it was through how I experience it — the five senses.

So I explore the property with each thoughtful step and with acute attention to the senses of touch, taste, smell, sound and sight. I hope that you enjoy these small glimpses into the remarkable beauty of Fly Ranch.

Water

When you think of the arid Great Basin, standing water isn’t the first thing that comes to mind. It’s more like sagebrush, howling winds and dust.

But surprisingly, there are wetland oases and high water tables, and Fly Ranch has both! It is one of the largest wetland areas in the region — if not the largest. With the help of some human modifications over the years, there are also perennial reservoirs fed from local aquifers and creeks born from the Granite mountain range.

The winter of 2017 was a monumental time for rain and snow in Nevada, breaking records in both the magnitude and frequency of precipitation. All dry playas became lakes, reservoirs filled to their brims, and lakes surpassed the high water marks that were longing to feel water again after years of drought.

The winter of 2017 was a monumental time for rain and snow in Nevada, breaking records in both the magnitude and frequency of precipitation. All dry playas became lakes, reservoirs filled to their brims, and lakes surpassed the high water marks that were longing to feel water again after years of drought.

I knew that I would experience the Hualapai valley in a state that hadn’t been seen for nearly 30 years. Also, arriving in mid April, I knew that weather patterns would be unpredictable at best, and definitely unlike anything that I had experienced in my past 11 years of building, attending and tearing down Black Rock City in August and September.

The air was cold and brisk. The snow levels on the Granite Range were at the lowest elevation in recent memory, and this pattern showed no signs of breaking until the final snow in early June.

Actually, at the time of writing this in mid-July, there are still some small patches of snow on the Granites. The dry hot air and winds that characterize Nevadan summers are here again, but the influence of all of the water this winter is still tangible.

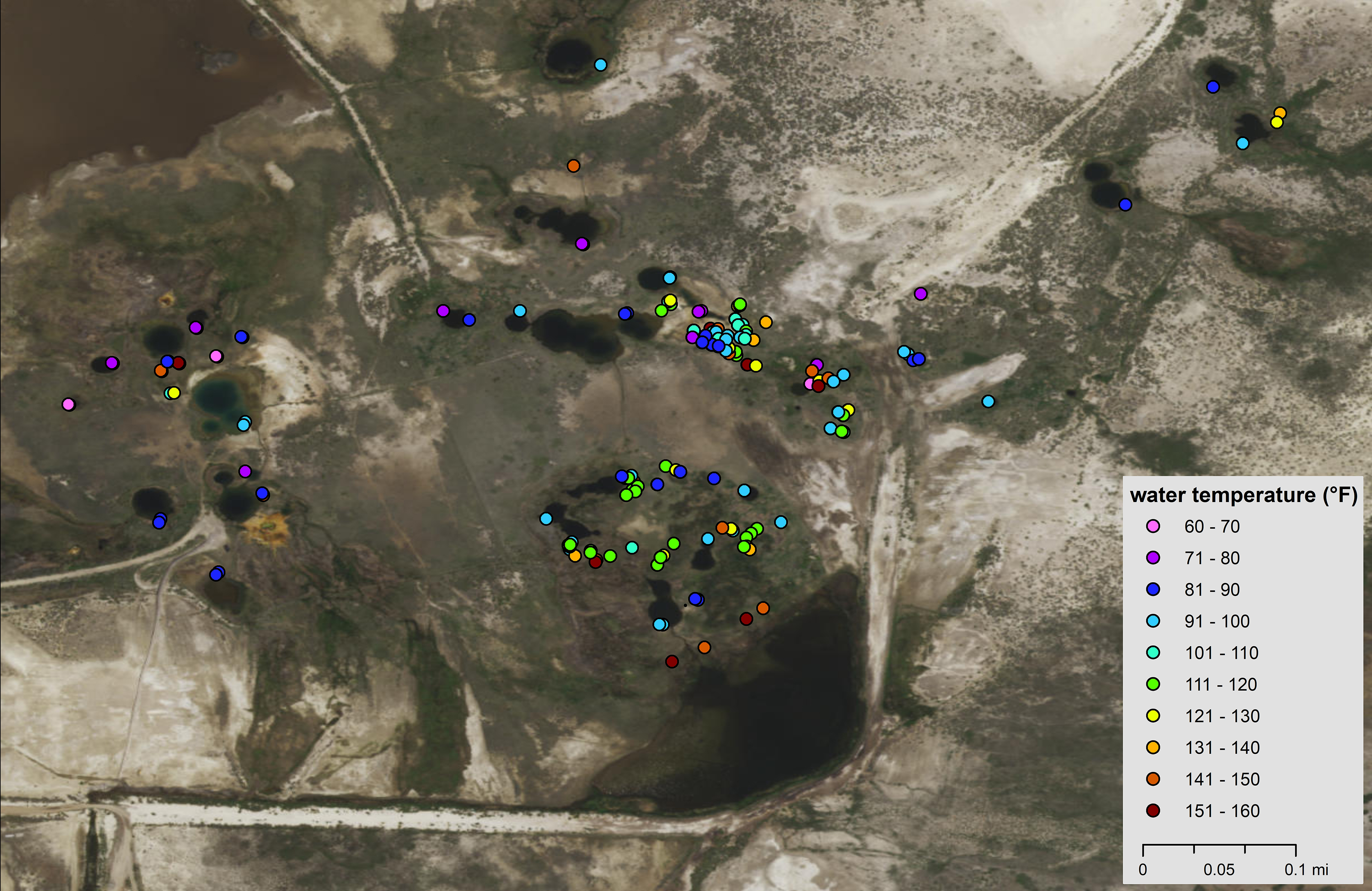

Fly Ranch is renowned for its geothermal features, some naturally occurring and some influenced by drilling explorations. The property is peppered with ponds of varying temperatures. I was told that there were 21 of them and I sought them out with my knee boots on and a GPS unit and thermometer in hand.

I didn’t expect to find over 90 bodies of water in just one square kilometer, ranging in size from a dinner plate to a large reservoir and with temperatures ranging from 70 to 158F.

The majority of them are smaller than a dinner table and are well over 110F. I dubbed them ‘hot holes’, having never experienced anything quite like this in my 20 years of studying wetlands.

There is apparently no rhyme or reason to their distribution, with cooler holes right next to the hottest holes, and their origin seems unknown. They could be the result of past drilling activities or simply naturally occurring due to their sheer number and lack of pattern — the jury is still out.

Some are connected by shallow creeks that gradually drain them from north to south (and eventually combine with other water that fills the trucks used to water the streets of Black Rock City).

Most are surrounded by either a thin veneer of wetland vegetation or an entire marsh that masks the small hot holes. Others stand alone, inconspicuous amongst the salt grass.

The influence of this hot water is even apparent in the early spring — much of the wetland vegetation that normally lies dormant and looks like a matted thatch of dead plants is vibrantly green and several feet tall.

This temperature influence is still apparent in mid July — where my feet feel warm through my boots, the stands of common three-square, a cosmopolitan wetland sedge, are over seven feet tall. This is twice as tall as what I’m used to seeing!

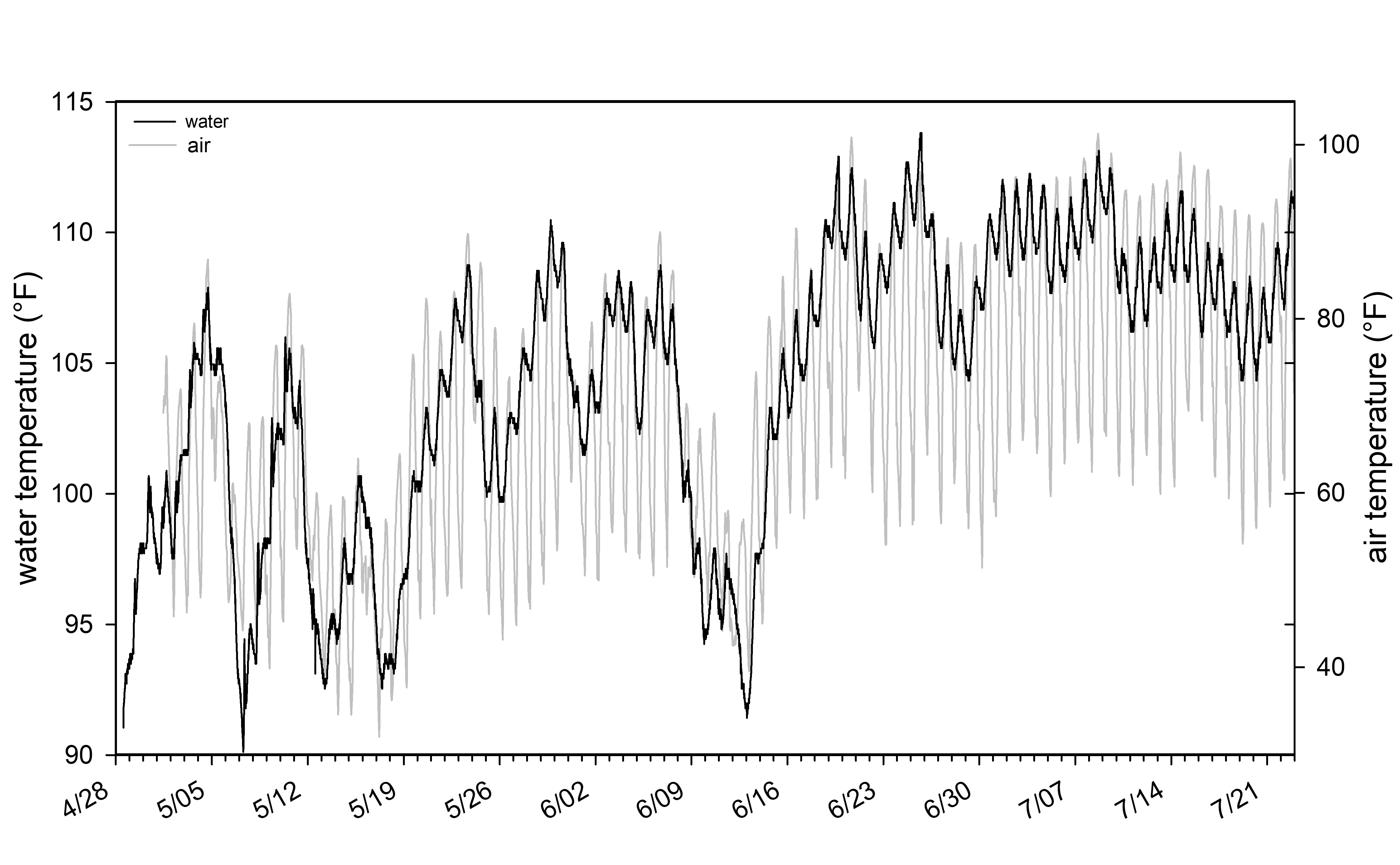

I was also surprised by the constant change of temperature that occurred within a pond, both on a daily and weekly basis. For instance, a larger pond that had previously been a swimming hole ranges from 90 to 114 F, tracking changes in the air temperature with almost precision accuracy.

Animal Tracks

As you might expect, all of the water has influenced the soils of Fly Ranch in more ways than one. Although I wasn’t here for the majority of the precipitation, the history of water and the touch of animals and birds were apparent in the tracks left behind.

Along the edges of the Hualapai playa, which is just now drying out, and across the many creeks that bisect the property, I saw signs of bobcat, mountain lion, Canada geese, American avocet, wild horses, mule deer, Pronghorn antelope and the ever-wily coyote.

Slightly higher in elevation, cattle tracks create their own cloven-hoof meanders throughout the sagebrush steppe, and the scratches of jackrabbits and cottontail dot the ground. Sinuous snake tracks and tail marks from long-nosed leopard lizards and Great Basin whiptails track the sandier soils.

Many animal and reptile holes of various sizes are common as well. Outside of the antelope ground squirrel holes, I’m still learning who the majority of inhabitants are.

I also see signs of human prints across the property. Some are along the Hualapai playa (including my own), some are where cattle ranching occurs, but the majority are near the geysers. The impact of this treading will be apparent for years to come.

I also see signs of human prints across the property. Some are along the Hualapai playa (including my own), some are where cattle ranching occurs, but the majority are near the geysers. The impact of this treading will be apparent for years to come.

This serves as your friendly public service reminder to not visit Fly Ranch at this time. Please be patient and please don’t enter the property by yourself.

Fences

A common feature lining the landscape of rural Nevada is the barbed wire fence. Thousands of miles of fence delineate the land with its simple design and goal to keep large animals and humans out with a prickly, effective touch.

On Fly Ranch, there are nearly 14 miles of fence along roads, surrounding pastures and the old ranch house, and protecting ponds from cattle and horses. Good fences make good neighbors, right?

On Fly Ranch, there are nearly 14 miles of fence along roads, surrounding pastures and the old ranch house, and protecting ponds from cattle and horses. Good fences make good neighbors, right?

Some animals have learned tricks to circumvent the piercing of the fence. I’ve seen rabbits and coyotes skirt just below the bottom line, and mule deer and antelope effortlessly hop over the top as if lifted by a marionette.

Some animals aren’t so fortunate; they get snagged by the wire while jumping, and are left at the mercy of the elements and the carnivores.

Every fence has its signature style. Some are simple with just T-stakes and barbed-wire, others are a combination of the latter with sturdy wooden poles every so often, and some are made with whatever wood is around — cowboy ingenuity at its best.

The old fences made entirely of wooden posts still line some of the eastern portions of the property. The wire has since rusted or busted off, creating a tricky and sometimes hidden maze of metal and spike. Dry rot and playa lakes have created lines of fallen posts, each with their aged signature of weathering.

The hard work and exertion of pounding T-stakes, digging holes and wrapping wire are not lost on this desert explorer, and I truly appreciate the rustic art seen at some fence corners .

Although the fences are designed to keep many things out, there is still is an active transfer of energy across these linear features. There always seems to be some way to get through, given some perseverance and perhaps some sweat and blood. Nothing seems quite permanent in the land of sagebrush, howling winds, dust and hot holes.