The Future of Fly

August 12, 2019Design the Future of Fly Ranch – Starting NOW!

January 14, 2020Renewable Energy Can Be Beautiful. Just Ask the Founders of LAGI

Elizabeth Monoian and Robert Ferry were just a floor apart at Carnegie Mellon University but never met. Two years later, they found themselves just a floor apart again — this time in an office building in downtown Pittsburgh. An elevator finally conspired to get them together. A conversation in the lift led to falling in […]

Elizabeth Monoian and Robert Ferry were just a floor apart at Carnegie Mellon University but never met. Two years later, they found themselves just a floor apart again — this time in an office building in downtown Pittsburgh. An elevator finally conspired to get them together. A conversation in the lift led to falling in love, getting married, and eventually launching the Land Art Generator Initiative (LAGI).

Conceptualized in 2008, LAGI invites interdisciplinary teams from around the world to reimagine our energy and sustainable landscapes as public art and places of beauty, all in response to local culture. The first design challenge kicked off in 2010 in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, and challenges have occurred every other year thereafter, in Freshkills Park, New York City (2012); at Refshaleøen in Copenhagen, Denmark (2014); next to the Santa Monica Pier in Southern California (2016); at St. Kilda Triangle in Melbourne, Australia (2018), and in Masdar City, Abu Dhabi (a special off-year edition in 2019).

Thrillingly, the 2020 challenge is going to be the Initiative’s first remote desert site…at Fly Ranch, right near the site of Black Rock City in Northern Nevada. You are invited to participate! Design guidelines will be released on January 15, 2020, and the challenge closes on May 31, 2020. LAGI 2020 Fly Ranch calls for creative and circular design solutions for energy, water, food, shelter, and regeneration (zero waste). $150,000 in awards will be distributed to selected teams for the purpose of building a functional prototype on site in 2021.

Thrillingly, the 2020 challenge is going to be the Initiative’s first remote desert site…at Fly Ranch, right near the site of Black Rock City in Northern Nevada. You are invited to participate! Design guidelines will be released on January 15, 2020, and the challenge closes on May 31, 2020. LAGI 2020 Fly Ranch calls for creative and circular design solutions for energy, water, food, shelter, and regeneration (zero waste). $150,000 in awards will be distributed to selected teams for the purpose of building a functional prototype on site in 2021.

To get your windmill turning, we caught up with Elizabeth and Robert to learn more about LAGI, to see some examples of projects come to life, and to get inspired for our climate future. Yes, we said “inspired.” As you’ll read below, Elizabeth and Robert believe the only way to solve our planet’s environmental challenges is through creativity, positivity, and hope.

Mia Quagliarello: What is the mission of the Land Art Generator Initiative?

Robert Ferry: The Land Art Generator is providing a platform for creatives around the world: artists, architects, engineers, scientists, landscape architects, et cetera, to be a part of designing our post-carbon future and the infrastructure that it requires. Renewable energy technologies like solar panels and wind turbines are an important component of the energy transition — a key part of solving the climate crisis.

However, there are some places where local communities are not involved in the planning process, or there’s an aesthetic pushback to installing renewable energy in cherished places. Solar and wind don’t pollute the air, so they can be very close to the places we live. A 100% renewable energy and post-carbon world is going to be one in which these infrastructures are all around us, so we need to start thinking about what they look like and how they relate to human culture. By presenting amazing examples of beautifully designed renewable energy and other sustainable infrastructures, we can inspire the public about how awesome this transition is. It’s not about sacrifice and asceticism.

Mia: What’s an example of what this looks like?

Robert: We have thousands of examples on the website of renewable energy designed as art in public space. Take for example solar technologies, which are incredibly versatile. It’s not just the flat blue panels that immediately come to mind. There are also thin films that are flexible, semi-translucent, and come in a variety of colors. You can print any image you want onto a solar panel so it can look like a mural on the side of a building. In this way, these technologies can actually be the media for creative expression.

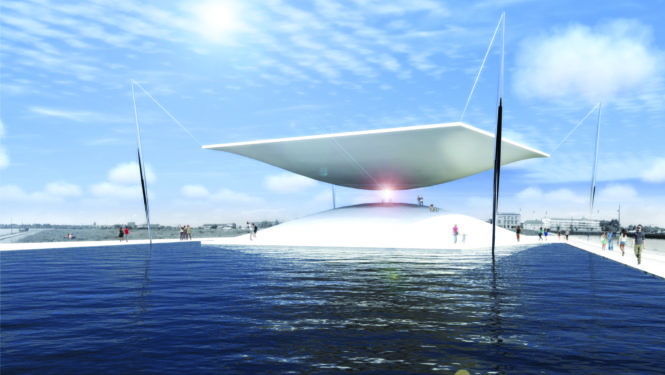

Elizabeth Monoian: Our very first submission that came in for LAGI 2010 in Dubai and Abu Dhabi is The Solar Eco System. Imagine a huge giant sphere made with gold-tinted photovoltaic cut out into an arabesque pattern — a new sun for the city of Abu Dhabi that itself is a power plant. Another great example is the Solar Hourglass.

Robert: That winning entry to LAGI 2014 Copenhagen uses concentrated solar power thermal technology that takes the heat of the sun, concentrates it into a single vertical beam of light that, in its visual image, looks like sand falling from the top to the bottom bowl of an hourglass. So you have this extreme beam of light — the power of a thousand suns — that’s actually powering a thousand homes while reminding us all that there’s still time to avert the worst effects of climate change. It provides an optimistic message and a beautiful place in the city for people to visit. You can actually get right up to that beam of light — so close to it that you can feel the heat and understand how the technology works (it’s protected by a cylindrical structural glass so that you don’t burn your arm off).

This is one of the things that’s really important to us, because there’s a cultural disconnect: People flip the switch on the wall to turn the light on, and they have no idea where that electricity is coming from. We need to span that gap during the energy transition so people have a clear understanding and cultural connection to where their energy is produced, how it’s produced, and who it affects.

Elizabeth: And at the same time, it’s critical that there is a message of optimism. We all know the doom-and-gloom scenarios, but research shows that that shuts people down to action. So, how can we reimagine our future in positive and optimistic ways? LAGI provides that platform.

Click on photos to see details

Mia: How did you get connected to Burning Man Project? Are you guys Burners?

Robert: We are now. [Laughter]

Elizabeth: Yeah, we are now! We got this really interesting email about two years ago from someone in the Burning Man community asking how we choose sites for design challenges. Over the course of some phone calls with Zac [Cirivello, Fly Ranch Operations Manager], we got connected to a June event at Fly Ranch, which was one of the first weekends that it opened up to folks.

That’s when we started connecting the dots between Fly Ranch and Burning Man. It all came together in that moment. So we were not Burners then, but we’ve participated in the last two, warmly welcomed into two camps.

Robert: We fell in love with everybody there and everything about it that first weekend at Fly, but we were such n00bs that we were sitting around the fire with Marian [Goodell, CEO, Burning Man Project] and other cultural founders and people were asking us if we were going to the Burn this year. We had to ask, “When is it?” because we had no idea. [Laughter]

Mia: With regards to the Fly Ranch challenge, aside from familiarizing themselves with all the materials and guidelines coming out on January 15, what advice would you give to applicants?

Robert: One really exciting thing that we’ll have this year that we haven’t had any year before is 3D object land mapping information. A guy named Steve Tietze went out [to Fly Ranch] with drones and basically mapped the primary design site areas in three dimensions, so teams will have access to that information to create virtual reality, augmented reality files and other visualizations.

But overall, it’s really important to understand the nature of the place and respect that it’s traditional Paiute land. Understand its context in the history of Burning Man as a community and its relationship to the town of Gerlach. It’s important to respect that culture, as well, and in the broader context of Nevada and the high deserts in the United States.

We know that some people will bring pre-established ideas about how to design sustainably in new places, but we hope that they’ll adapt those ideas to specific contexts of Fly Ranch rather than lay their ideas onto the place.

Elizabeth: Outside of that local context, we want participants to feel a sense of urgency. We are at a critical moment globally, and we must address one of the biggest challenges that humankind has had to deal with. We help our teams really jump into that urgency with enthusiasm and optimism.

Click on photos to see details

Mia: You’ve mentioned “teams” several times, but what if an individual wants to get involved? Is that possible?

Elizabeth: Actually, some of the best ideas come from individuals. “Solar Hourglass” is a good example. We encourage interdisciplinary teams because we think artists can gain a lot working with engineers and scientists, and engineers can gain a lot from working with artists. Interdisciplinary collaboration always leads to a strong outcome. If individuals are looking to connect with teams, they can reach out to us and we might be able to help connect them.

Mia: What if someone is 100% new to all this? They’re not an architect, a designer, or an environmental scientist. How can they be involved?

Elizabeth: Yes! We love for people who are new to this conversation to jump into it. Again, they might want to reach out to us directly and ask for guidance. We are available, and we answer every single email.

Robert: It’s free to enter. There’s no barrier to entry and anyone can do so. You don’t have to have Maya or Rhino or 3D rendering skills. We love hand-drawn proposals, and the photorealistic quality of renderings is not a criteria in the selection. It’s all about the idea.

Mia: In your blog, you talked about the “2010s as the decade of hope and the 2020s as a decade of action.” How do you see that action playing out in the next decade?

Robert: You’ve got to be optimistic, and there’s a lot of signs pointing in a great direction. Just in terms of the cost of solar and wind technologies — in just a couple of years from now, it’ll be cheaper to build new solar infrastructure than to maintain existing incumbent energy infrastructures. So we’re going to see the transition increase rapidly. We’re excited by how creatives and artists and architects are really embracing the energy transition.

Elizabeth: As we enter this decade of action and deep transition, it’s very important that many voices are at the table, that folks not be left behind. The questions are: Who will benefit in this transition? And how does this transition impact our landscapes and culture? We do see that there’s a terrific opportunity for creatives to be at the helm of that transition. The Hoover Dam is a great example.

Robert: We often point to the original New Deal and the Works Progress Administration, which employed tens of thousands of American artists to participate in the design of that generation’s infrastructure, which we all still enjoy today. Visiting Hoover Dam, you see beautiful works of Art Deco sculpture set against that amazing landscape. Folks visit that in the millions a year, not to necessarily geek out on hydro electric technology but to see the beauty of the architecture and the artwork. There’s an opportunity in the next couple of decades to do the same thing and create a lasting legacy for future generations to visit by the millions.

If we miss that opportunity, it will be incredibly unfortunate. It will also serve to hold us back in the acceleration of the transition. The more we can inspire the general public and give people something to run towards rather than just run away from, the faster we’ll actually implement these changes.

Elizabeth: It’s important that communities feel engaged with the design of their energy landscapes. What we’re learning from case study after case study is that even if renewable energy projects are well planned and well intentioned, if the community is not involved in some way, [the installations] are more likely to fail. That could be because there’s pushback because of the visual impact. It could be that there isn’t a community who’s trained to take over the maintenance of that installation. There’s a wide range of reasons that community must be involved in the conversation around these energy landscapes. As we enter this decade of action, everyone must be invited to have a seat at the table.

Further Reading and Resources

Books:

- The Soil Will Save Us: How Scientist, Farmers, and Foodies Are Healing the Soil to Save the Planet, by Kristin Ohlson

- The New Carbon Architecture: Building to Cool the Climate, by Bruce King

- Net Zero Energy Building: Predicted and Unintended Consequences, by Ming Hu

- An Organic Architecture, by Frank Lloyd Wright

- This Changes Everything, by Naomi Klein

- The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming, by David Wallace Wells

- Land and Environmental Art, by Jeffrey Kastner and Brian Wallis

- Destination Art, by Amy Dempsey

- The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind, by William Kamkwamba and Bryan Mealer

- The Poetics of Space, by Gaston Bachelard

- Art Parks: A Tour of America’s Sculpture Parks and Gardens, by Francesca Cigola

- Drawdown, edited by Paul Hawken

- Playa Dust: Collected Stories from Burning Man, edited by Samantha Krukowski

- Designing Climate Solutions: A Policy Guide for Low-Carbon Energy, by Hal Harvey

- Compass of the Ephemeral: Aerial Photography of Black Rock City, by Will Roger

- Desert to Dream: A Dozen Years of Burning Man Photography, by Barbara Traub

- Toward an Urban Ecology, by Kate Orff

- The Nature of Economies, by Jane Jacobs

- Writings on Landscape, Culture, and Society, by Frederick Law Olmsted

- Design With Nature, by Ian L. McHarg

- The Art of Burning Man, by NK Guy

- Return to the Source, edited by Elizabeth Monoian and Robert Ferry

- A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction, by Christopher Alexander

- Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, by Buckminster Fuller

- The Barefoot Architect, by Johan van Lengen

- The One-Straw Revolution, by Masanobu Fukuoka

- Mycelium Running, by Paul Stamets

- Permaculture, a Designer’s Manual, by Bill Mollison and Reny Mia Slay

- The Sustainable Sites Handbook, by Meg Calkins

- The Upcycle: Beyond Sustainability — Designing for Abundance, by William McDonough and Michael Braungart

- The Bio-Integrated Farm, by Shawn Jadrnicek and Stephanie Jadrnicek

- Massive Change, by Bruce Mau

- The Image of the City, by Kevin Lynch

- Playa Works: The Myth Of The Empty, by William Fox

- Earth-Mapping, by Edward Casey

- The Ecology of Freedom, by Murray Bookchin

- Silent Spring, by Rachel Carson

- Biophilia, by E.O. Wilson

Organizations, Websites and a Podcast: